Studying Effectively, Part 2 – Never Later

Now we’re back with the second part of how to study effectively, as I’ve learned from Coursera’s Learning to Learn module.

In the previous summary, we talked about the modes of thinking and how to “chunk” information. It didn’t take me that long to write this one up, and it’ll be obvious why in a few seconds. It’s because today’s focus is on procrastination!

Battling procrastination

Remember when we said that it is important to set aside time everyday to study? If you find yourself cleaning, cooking, reading, and doing everything except the one thing that you’re supposed to be doing (yes, that is studying!), then you are not alone.

We all know procrastination works because of the easy gratification we feel when we put aside something that causes us discomfort (e.g. such as learning something new) in favor of something pleasurable (e.g. watching TV). Sometimes, our fear of discomfort is greater than doing equally unpleasant chores, which is why we procrastinate by being more “productive.” In addition, if we have not been keeping up with our daily work in studying, we begin to make excuses, such as studying closer to an exam date to remember more details—activating only our short-term memory.

Beating procrastination requires a lot of self-awareness of the cues and/or triggers for our behaviors, our routine responses (or reflexes), our reward system, and our beliefs. Optimizing these four factors will help us battle procrastination. For cues, knowing what will help us focus and start studying as well as what will distract us (e.g. Internet browsing, phone notifications) is important. This way, we can set ourselves up for success. If we study better n a quiet place with everything organized, then our study place should be set like that prior to our scheduled time for study. Likewise, distractions should be put away.

Changing our routine responses involves rewiring our brains. For example, instead of reaching out for the phone when we hear a ping, we can resolve not to look at the notification and keep from typing out an immediate response. As for rewards, it may be helpful to focus on the benefit we will get by discipling ourselves in our study. We may bask in the pride of a job well done or relish in small pleasures, such as playing video games after a set study time or buying a new dress when we achieve our target exam scores.

It is also imperative that we quit our negative self-talk about our productivity and ability. Stop telling yourself that you’re better at exams when cramming. Hang out with good friends who will inspire yuo towards a better work ethic. Believeing taht you can accomplish something makes you more cognizant of the way to achieve it.

There are three more helpful tips that this course brings to stop procrastination. First, and probably the most important, is to not waste willpower. By reducing the opportunities for choices, you will not exhaust your willpower and will not have to feel like you have to beat procrastinating every second of your time. The second is to focus on not the finished product (the exam or project) but on the process of getting there. This will help you flow into the work and will make each session, however short, gratifying in itself.

Finally, and I am a fan of this: plan. Write down things that you need to do the night before. This frees up working memory and also helps, with sleep, consolidate an efficient plan for the next day. Planning also means knowing when to quit and rest and making time for leisure, which serves as extra motivation to get even the most tedious and difficult of tasks done.

In practice

I heavily use pretty planners, so writing things down for the week is something I usually do. I do not beat myself up for not checking off everything, but accomplishing most of it does give me a sense of pride and relief.

I think what has been best for me, with regards to procrastination, is being realistic about what I can do on a daily basis and accounting for my family’s needs, available hours, and personal health (e.g. am I burning out?). This way, if I can sit down and read a page (just a page!), I don’t feel too bad.

I also discipline myself to sit still and actually read and study, or even write, if I have to, as I have several writing jobs. If I can get through the first painful 10 minutes, I usually am good to go and find myself in the flow. Also, I only work at my desk in the office at the hospital, and very rarely at home. This separation of work and home life makes me productive and also allows me to be present when I’m at home. (Because, let’s face it, there are a lot of things to do at home! Cooking, cleaning, laundry… The list never ends.)

There is also a trick I do the night before a big day, be it cooking 6 different dishes in one go or grossing complex cancer cases. I’ve heard performers imagine themselves doing whatever it is they’re supposed to do, and it helps smoothen movements and improve flow. So I do the same! Several times over, integrating theory and practice (at least in my head). This way, when I’m at the scene, I can do it with little stress. This mental practice also frees up working memory, so I am more alert to things not going as planned, and I am more ready to solve them.

To reduce the stress on my willpower, I’ve also found that routine helps. I know, shocker! I used to be a spontaneous whatever-happens type of gal, always working in spurts and crashing and burning. However, I do not think this strategy works when one has a demanding career combined with a busy family life. The routine doesn’t have to fill my day, but it should be present when willpower is least: mornings, evenings before sleeping, upon reaching my desk, and that drowsy time after lunch. If you ask me, routines also free working memory and allows more room for work (or relaxation) to be done.

We’ve talked a lot about working memory, but what is it? And what is long-term memory? We talk about this in the next part. Don’t forget (pun intended) to check in. Until next time!

References

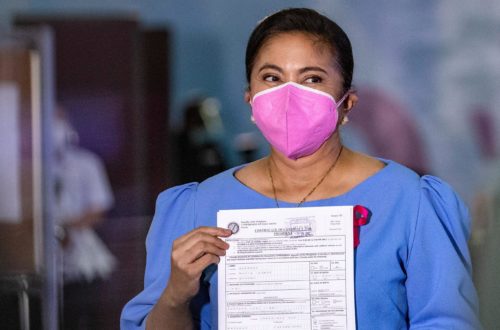

Photo by energepic.com.

See also