Research Paper Review: Imprint Cytology for Lymphoma Workup

Like I’ve promised, here’s the first paper that I’m reading that’s relevant to my current residency rotation!

While reading, however, I became uncertain of the format I’m supposed to take with each paper I read. On Eye Research Now, which is another website that I run and which consists of updates in ocular science and medicine, I tend to follow the abstract of the paper published. While reading this first paper, however, I’ve realized how much I don’t know and how I’ve been tempted to focus on the littlest of details. This makes me lose focus on the key message of the article. At the same time, I don’t want to simply skim the paper and get the takeaway.

That said, I’ve decided that I will simply offer the main point of the paper and then proceed to the concepts I’ve understood along the way.

Article details

Julien, L., & Michel, R. (2021). Imprint cytology: Invaluable technique to evaluate fresh specimens received in the pathology department for lymphoma workup. Cancer Cytopathology, 129(10), 759-771. doi: 10.1002/cncy.22442

Why this paper

This paper is a commentary co-written by one of the staff in our department, Dr. Rene Michel, and who has supervised me most days of the last two weeks of my current rotation. Dr. Michel is specialized in hematopathology, and he enjoys teaching medical students and residents. This publication was forwarded to the entire pathology department at McGill, as it was important that everyone who covered frozen sections would know what to do with specimens received for lymphoma workup.

Key points

- Imprint cytology is a valuable tool in evaluating specimens received for lymphoma workup. Whether the specimen is abundant or scant, imprint cytology helps in triaging tissue allocation for subsequent studies.

- Advantages of imprints include an easy preparation, with minimal distortion to the biopsy and to the specimen, and negligible tissue loss. Cytologic details are also well-preserved and have only a few artifacts.

- The lack of images for imprint cytology can prohibit its use in institutions not familiar with what microscopic findings to expect.

General approach to triaging specimens

- The preferred method for diagnosing lymphoma is evaluating an excisional biopsy of a lymph node. Clinical guidelines currently caution against the use of insufficient tissue in diagnostics, particularly with core biopsy and especially with fine needle aspiration.

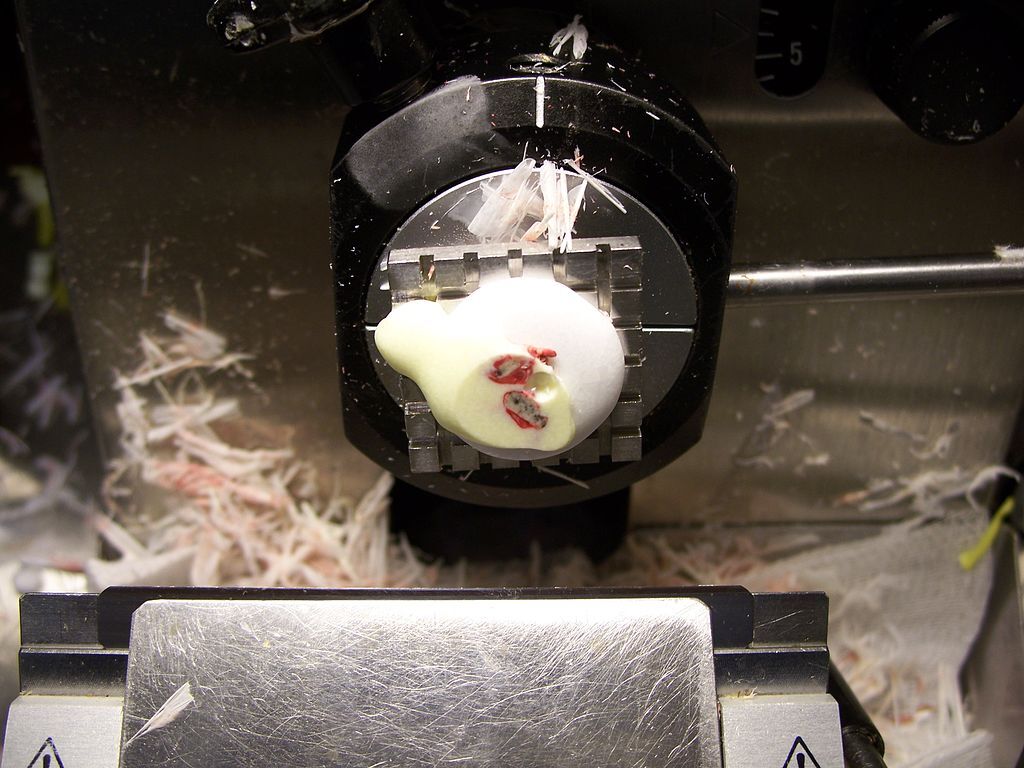

- Upon receiving a specimen, it is kept moist with saline, and a touch imprint is performed by lightly pressing a slide against the tissue surface. This is then fixed with methanol and stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

- If the imprint cytology shows non-lymphoid neoplastic cells, no further workup is necessary, and the rest of the tissue is fixed in formalin.

- If the imprint cytology shows granulomas, then it becomes necessary to check for infectious causes. Some tissue can be sent to the microbiology laboratory.

- Lastly, if imprint cytology shows lymphoid tissue, then tissue can be allocated as follows.

- Additional touch imprints are fixed in Carnoy solution for possible fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis. This is important in Burkitt’s lymphomas or in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas, where we want to check for MYC, BCL2, and/or BCL6 rearrangements.

- If there is sufficient tissue, a 1.5-cm core (or 3×3-mm tissue cube) can be kept in RPMI medium for flow cytometry for immunotyping. This may be indicated in low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphomas, in which clonality analyses can be done.

- Some tissue can also be snap frozen and stored at -80oC for molecular analyses (e.g. clonality and translocations). As a side note, it’s t(14;18) for follicular lymphoma and t(11;14) for mantle-cell lymphoma.

- For imprints showing cells that suggest Hodgkin’s or Reed-Sternberg cells, formalin fixation and paraffin embedding should be prioritized. This is because the diagnosis of Hodgkin’s lymphoma relies on such sections and on immunophenotyping by IHC.

Interpreting cytologic imprints

- General housekeeping

- Make sure the imprints match the tissue.

- Check quality of staining and absence of artifacts (air-drying, crushing).

- Observe cellularity and extracellular material (necrosis, mucin). If the imprint is paucicellular, this can suggest a nonlymphoid malignancy or fibrotic process that can be either reactive or malignant (e.g. sarcoma).

- In metastatic carcinoma, cells form distinct cohesive clusters or sheets of atypical cells and are usually larger than lymphoid cells.

- Beware of mimickers! Small, round, blue cell tumors can appear as lymphoma on imprints. If you see dispersed isolated cells that can also form loose aggregates, with nuclear molding, salt-and-pepper chromatin, it’s likely small cell carcinoma. Ewing sarcoma will have pseudorosettes with nuclear molding and a tigroid background. (Note that a lot of findings are hard to see on imprints.)

- In granulomatous inflammation, epithelioid histiocytes with elongated, spindle-shaped and/or curved (boomerang) nuclei, with abundant cytoplasm and indistinct cell borders, forming a syncytium, can be seen.

- What would suggest infection? Neutrophils, necrosis, debris, some multinucleated giant cells.

- Granulomatous inflammation is nonspecific and may also be associated with carcinomas and lymphomas. You must still search for atypical lymphoid or nonlymphoid cells.

- What do we see in reactive hyperplasia? Polymorphous lymphoid cells, with larger centroblasts, some histiocytes, tingible-body macrophages, and plasma cells. This, however, is contingent on the evaluation of architecture in permanent sections. This can also be seen in lymphomas.

- Monomorphous proliferations of lymphoid cells suggest a possible lymphoproliferative disorder. Infiltrates may be subdivided into possible etiologies based on the size (small, intermediate, or large).

- Small lymphocytes are characteristic of low-grade lymphomas and include entities such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), follicular lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, classic mantle cell lymphoma, and (rarely) lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma.

- More aggressive CLL has more prolymphocytes (larger cells with more nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm).

- Follicular lymphomas have predominantly small, cleaved lymphocytes (centrocytes). Larger centroblasts are seen in tumors with higher grades.

- Marginal zone B-cell lymphomas have heterogeneous populations of predominantly small lymphoid cells, with pale staining cytoplasm, some plasma cells, and large lymphocytes.

- Medium-sized lymphoid cells (2-2.5x the size of a small lymphocyte) include the blastoid variant of mantle cell lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma. Burkitt lymphoma cells are medium-sized, monotonous, with round or polygonal nuclei, and have a background of necrosis or apoptosis.

- Diffuse large B-cell lymphomas are frequently seen on imprints. Large cells (3-4x the normal size) are pleomorphic, with vesicular or coarse chromatin, and have prominent nucleoli.

What I thought

Wow, I didn’t realize that there were so many types of lymphomas! I’m sure I will learn about more, especially when I do my molecular pathology and hematopathology rotations.

I have personally done imprint cytology slides on core biopsies and on lymph nodes. It’s not difficult to do the initial H&E slide; the interpretation can be tricky, however, especially when the tissue provided is already scant. Thankfully, clinical history gives clues most of the time, and I don’t believe that the surgeons calling for intraoperative consultation expect a spot diagnosis of a lymphoma subtype.

As for reading research papers, I think this is good practice for me. It does take a lot of my time, but I hope to be more efficient at it through time.

Till the next paper!

References

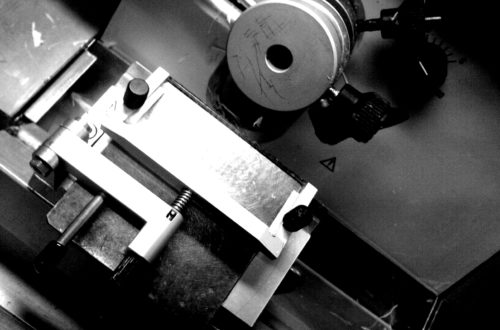

Featured image of tissue in a cryostat taken from the following source.