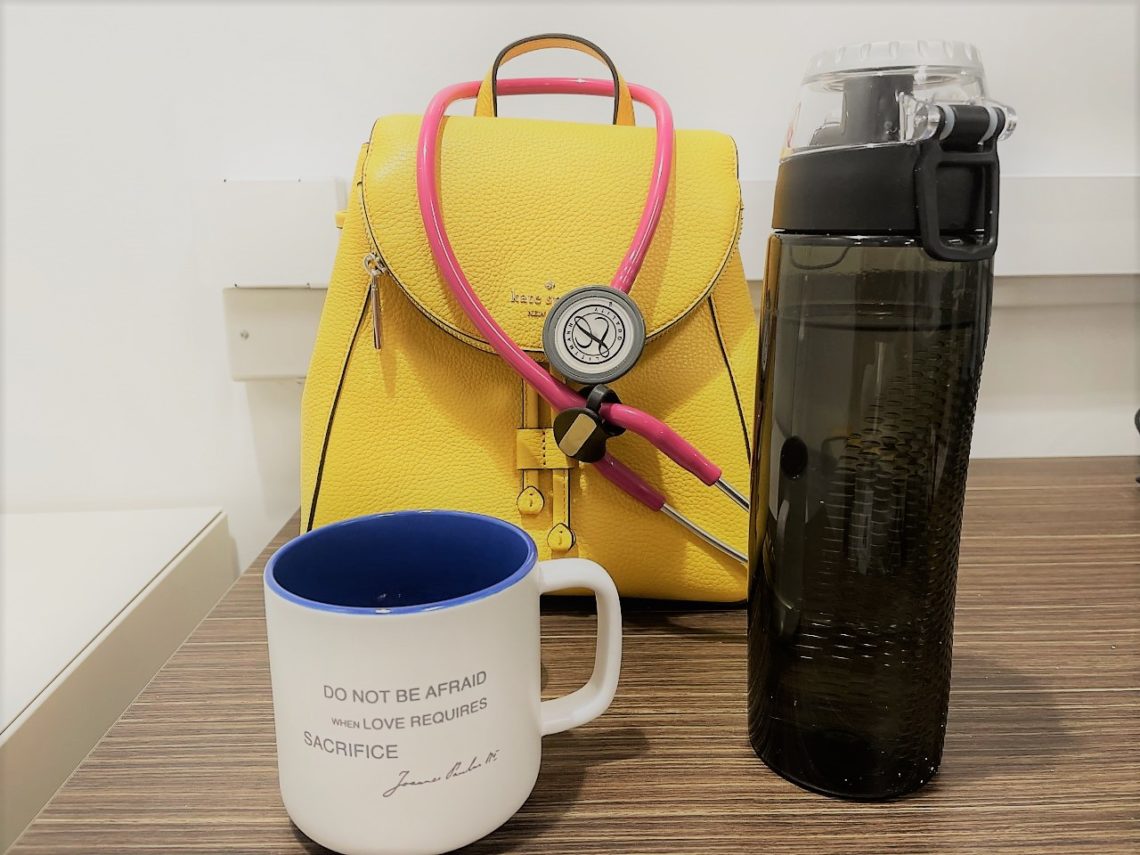

Back in Clinic

Believe it or not: the last three weeks, I have had my stethoscope hanging around my neck.

Knock, knock. Good morning (or afternoon), my name is Dr. Lasiste, I’m working with Dr. Staff today… Is it okay if I ask you a few questions first and examine you, and then Dr. Staff and I will be back in to see talk to you? So has my usual script gone, making me feel as if I’m in school or doing my OSCE again.

This month, I’m back in clinics, seeing patients with the Medical Oncology staff. My time spent here has, unexpectedly, been wonderful for several reasons. First, the staff like to teach, and they also try to tailor their teaching to what they think is relevant for me as a future pathologist. Second, reading pathology alongside seeing patients helps me consolidate my knowledge, and it is also useful for me to correlate what I read with what manifests clinically in patients and what affects decision-making by the physicians treating them. In fact, it’s funny how sometimes, I talk to patients, and upon reading their pathology results I can summon an image of what the tumor may have looked like under the microscope! (Of course, this only applies to those that I’ve somehow read about.) Third, it is fulfilling to be able to use the lessons I have learned in my five years of medical school, particularly the art of history-taking and physical examination. It’s funny how some things never leave one’s brain, and even during the second day muscle memory kicked in.

I say second day, because on my first day in clinic, I actually forgot my stethoscope! The clinician I was working with gave me a pass with a casual shrug after saying, ” Ah, pathology.”

This rotation also meant longer commutes, just because I’m in a hospital that’s further away from where I live. On really bad days, it would take me two hours(!) to drive one-way to work. On great days, just an hour. Prior to this rotation, I have been listening to my forensic pathology podcasts (because which person doesn’t like a good story of solving crime). I was, however, getting bored of the content, so I tried switching to audiobooks instead and first attempted one on parenting. A few chapters in, however, and I wasn’t sold.

Then I remembered a book that I had purchase while I was on maternity leave, one that I had intended to read but never got around to because I didn’t have time to read an actual book that needed light. (I could only read e-books in dark mode while trying to send my daughter to sleep.) It was a giant tome, titled The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of Cancer, and was written by a medical oncologist named Siddhartha Mukherjee. And I thought to myself: what better way to spend my commute during this rotation than listen to this audiobook?

I was blown away by the scope and detail of this book. Here are some random thoughts that I had while listening to this audiobook.

- We take so much of what we now know for granted. I didn’t realize that until soon after the second world war, scientists didn’t really have a good conceptual grasp of the molecular underpinnings of cancer. For example: mutations, the ineffectiveness of radical surgeries in metastatic disease, the impact of chemotherapy on normal cells on the body, the interactions between the immune system and the microenvironment and malignant cells. It was so much fun listening to the history of scientific thought on cancer as a disease; all the twists and turns has led us to where we are today, with a gamut of chemotherapeutic options, as well as surgery and radiotherapy, to manage and sometimes even cure this illness.

- Dr. Sidney Farber was a visionary. I am very proud of the fact that he was a pathologist by training, and I hope that when I finish my training and am a practicing pathologist, I never lose sight of the patients that I care for, even if I do so from a distance. His vision of defeating cancer and how he responded to obstacles in his way has made me rethink my smallness of mind. Now I suppose that when I do encounter a great idea, I will not be scared by the sense of purpose and the task that needs to be accomplished.

There is one last part, perhaps the most important, about my rotation in medical oncology: the stories.

I had forgotten how impactful listening to people’s stories can be—and in this clinic, where patients fight what is likely the battle of their lives, the stories are achingly haunting and inspiring at the same time. There is that South Asian woman who refused adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery and tried alternative medicine, only to come back more than a year after with distant metastasis, weak and frail and pleading for a cure. There are the women with metastatic breast cancer who have been responding well to chemotherapy or immunotherapy drugs, whether established or experimental, who have enough energy and strength to publish books, sing at theater, or make it their personal mission to reach out to others afflicted with the same disease. There are the men with widespread pancreatic cancer who have been given third-line medications and have not responded, who have been given the news that there are no more options, that basically we are waiting for the disease to progress and overwhelm them. One cried silently, dignified, with the realization that he will not even get palliative surgery for his hernia to make the last of his life more comfortable, and then he spoke of how he wanted to be there for his daughter who was to be married. There were men who were newly diagnosed with cancer, grappling with the reality beside their wives, and women who have emerged triumphant from stereotactic brain surgery for metastatic intracranial disease, whose husbands have left them to fend for themselves. There were a lot of tears: happy and sad, and whatever laughter there was from patients, I felt were present more to comfort the doctors than a truthful indication of their mood.

These patients, who embody graceful strength and who are so generous (especially now with the holidays approaching), are the reminder why clinical medicine is so fulfilling… and also why I opted out of it.

I see now, with great foresight, that if I were to do this for the rest of my life, I would crumble under the emotional weight (and the bureaucracy of papers) likely even before I finish training.

How do you this? I ask residents, fellows, staff physicians. How?

I watch them converse with patients, taking cue from their disposition, and patiently attempting to address all their questions, their fears, their concerns. I see them carry thick charts, only to write on even more pieces of paper, to stay on top of monitoring cancer for progression and recurrence. At the end of a day in clinic, I feel exhausted from being on my feet (we have standing workstations) and from the emotional rollercoaster of talking to patients. And to think that I have faced cancer with them in but at most the half hour of their appointment!

It’s both happy and sad, the clinicians have told me. And we’re making progress with cancer. Some things I never would have thought possible when I was in school are possible now.

It’s an honor, others have emphasized, to be treating these patients.

There have also been occasions where I, as a pathology resident, have been of help. Some have been more mundane things, such as locating pathology results done in another hospital. Some have been through me being able to afford a more detailed pathophysiology when necessarily questioned by either colleague or patient. Sometimes, I have been privy (inadvertently or otherwise) to conversations between clinicians when they’re discussing the shortcomings of the pathology department. I listen closely when I hear these subjects, as these are potential areas for improvement… and also for my quality control/quality assurance research project that is a requirement in residency, ha!

As this is one of the last clinical rotations I will do before I return to the world of pathology, I take my sweet time when seeing patients. I take all the time I need, so much so that I receive compliments on how wonderful it is to have a doctor who carefully asks questions, gently examines, and simply listens. Patients say that I do well what I do. I courteously say thank you, a bit embarrassed by the trust placed in me. But in moments of silence, away from the busy humming of clinics, when I can actually hear myself think and cannot be charmed by the gratification of being front and center, I am happy and relieved to be behind the scenes, setting the stage.

To my future patients, I will retire my stethoscope, but know that I will train so I can better serve with my microscope. And should you think that you’re alone facing this monster of an illness, know that I have already stared in its face and wept with you. I will likely be with you every step of the way. And should you finally conquer, I will already have rejoiced with you.

When I’m ready, there will no knock, knock. Just the description and diagnosis that your clinician needs, signed by your pathologist, Dr. Lasiste.